“What would happen if we could instantly access all the information we were exposed to throughout our lives? If there were a way to recall everything you once knew about someone you are going to see again for the first time in twenty years? If you could tell your doctor everything you had eaten in the week before you broke out in hives, both yesterday and six months ago?” - Bill Gates [1]

At face value, the term “data hoarding” is more than likely to evoke pejorative associations. With its linguistic and conceptual proximity to analogue hoarding, it can likewise be interpreted as pathological or excessive accumulation. However, within digital communities—particularly those on platforms such as Reddit, and namely r/DataHoarder [2], there exists a vibrant subculture of self-proclaimed "data hoarders," who openly discuss and display, with pride, vast, meticulously or haphazardly collected repositories of digital content.

Not only the content is paraded, the vast and elaborate, frequently 'home-lab-esque' infrastructure is presented, some users boasting multiple petabytes of storage.

What is data hoarding?

Formally, data hoarding is defined as:

"the acquisition of and failure to discard digital content, leading to accumulation of digital clutter" [3]

One of the 'smaller' setups on this subreddit! View original Reddit post on r/DataHoarder

One of the (slightly) larger setups on this subreddit! View original Reddit post on r/DataHoarder

So, is doing so good, or bad?

Let’s instead ask a more meaningful question: why do we feel compelled to keep things at all?

I would argue the framing of “good” or “bad” resists nuance—and more importantly, misses the point. The deeper question isn’t moral, but human: what is the value we assign to what we choose to hold onto?

As Gordon Bell and Jim Gemmell put it in their reflections on MyLifeBits:

“Supposing one did keep virtually everything – would there be any value to it? Well, there is an existence proof of value. The following exist in abundance: shoeboxes full of photos, photo albums & framed photos, home movies/videos, old bundles of letters, bookshelves and filing cabinets.” [4]

And rightly so.

“While many items may be accessed only infrequently (perhaps just a handful of times in a lifetime) they are treasured; given only one thing that could be saved as their house burns down, many people would grab their photo albums or such memorabilia.” [4]

This reflection does not advocate for hoarding, nor does it seek to romanticise accumulation. But it must be acknowledged: the impulse to preserve is deeply human. In contrast to earlier eras where storage was physical, finite, and burdensome, today’s digital data takes up negligible space. It demands little of us. So why shouldn’t someone save what they perceive as meaningful?

After all, who are we—as observers removed from the context of someone else’s memories—to decide what is or isn’t valuable? If a fragment holds resonance, it deserves to be kept. Sometimes, collecting digital artefacts is no more complicated than the instinct to pocket a shell from the beach: it’s not about utility; it’s about a quiet act of noticing, and choosing to keep a moment close.

"2000 rolls (9 inch x 250 feet) of aerial film taken from the 1950s and later" — 'analog' hoard View original Reddit post on r/DataHoarder

A thousand-page document once required literal shelf space—precisely the constraint Vannevar Bush sought to overcome with his 1945 Memex vision, which he described as “a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanised so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility,”[5] noting that “if the user inserted 5000 pages of material a day it would take him hundreds of years to fill the repository, so that he can be profligate and enter material freely”[5]. Similar volumes of information can now be stored billions of times over on micro-scale media.

Bush went further to illustrate the power of microfilm [6] (a constitution of photographic film, purposed for document transmission, storage, reading, and printing) compression: “The Encyclopaedia Britannica could be reduced to the volume of a matchbox. A library of a million volumes could be compressed into one end of a desk” [5]. Today’s file systems—NTFS supporting up to 8 PB (8,000TB) on Windows Server [7], ext4 with a practical limit of an entire exabyte (1000PB!) [8] — realise and far exceed Bush’s original vision.

You may be inclined to think you require a datacentre in your own home to store content on mass digitally, but something as small as this Raspberry Pi NAS could easily store 12TB with even only 2.5" HDDs/SSDs (and potentially more!) Raspberry Pi Official Magazine

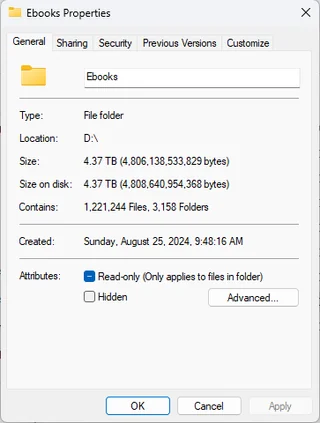

Data Hoarding could only come into fruition due to content dematerialisation

This dematerialisation of content complicates our cognitive engagement with digital information. Absent a physical presence, digital data is easily amassed without consideration or curation [4, 9]. The former ritual of choosing which books to fit into an overstuffed suitcase has been replaced by the ability to carry an entire library in one’s pocket, leaving decisions of consumption deferred and unconstrained.

A ~4.5TB ebook hoard View original Reddit post on r/DataHoarder

While it is tempting to elaborate endlessly on this transformation, there is a more pertinent consideration. The vast capacity of digital storage opens possibilities not only for indiscriminate accumulation but also for meaningful documentation. Here emerges the concept of lifelogging—the systematic or ambient recording of personal data over time.

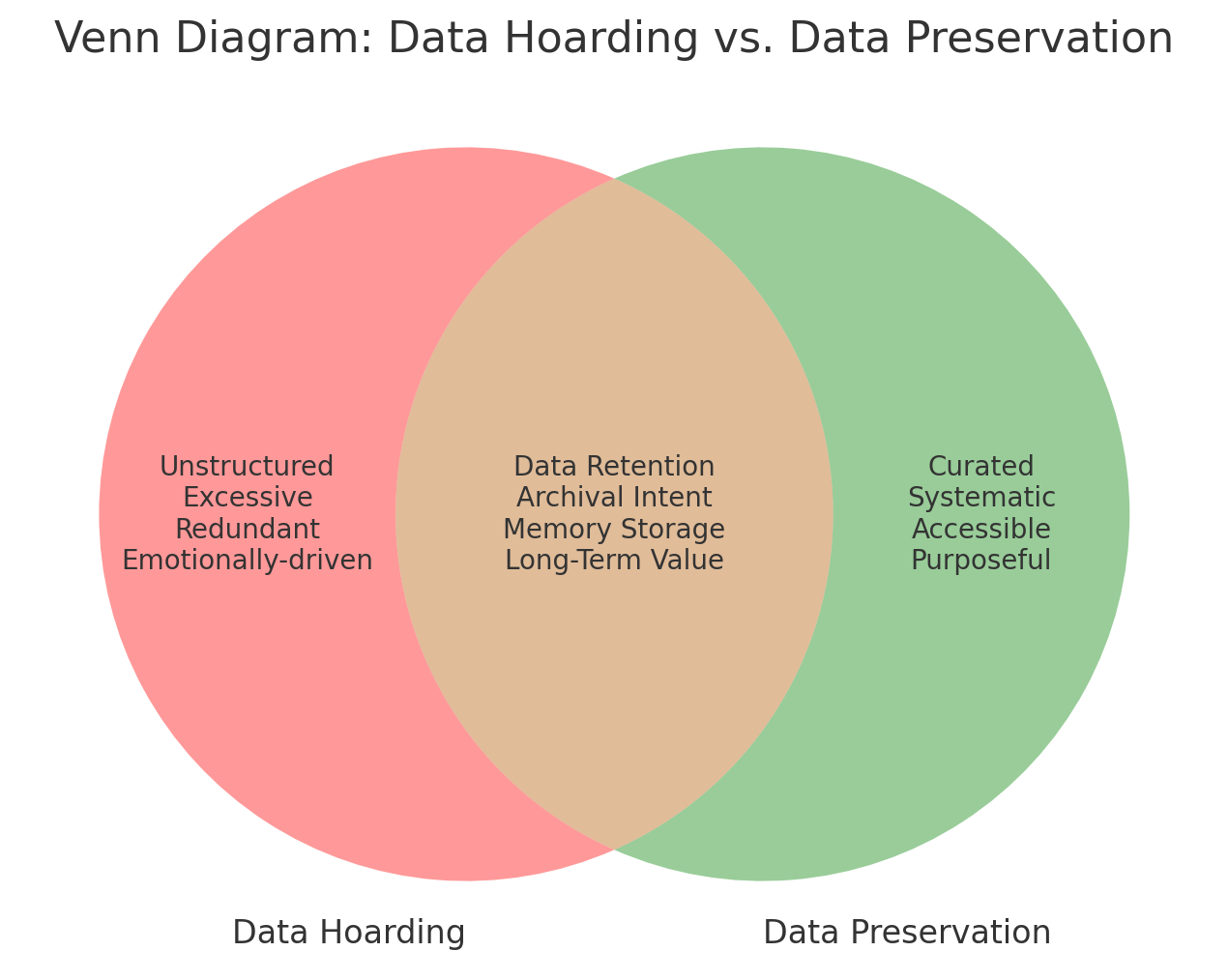

Data hoarding vs. Data preservation?

In this context, data hoarding and data preservation begin to intersect. If data preservation is the cultivated, systematised cousin of data-hoarding —dressed sharply, tie knotted with precision—then data hoarding remains its unruly, eccentric relative. Both, however, engage avidly with the central act of data retention.

This is to be taken with a pinch of salt, and there is nuance in each case (I made this diagram with AI)

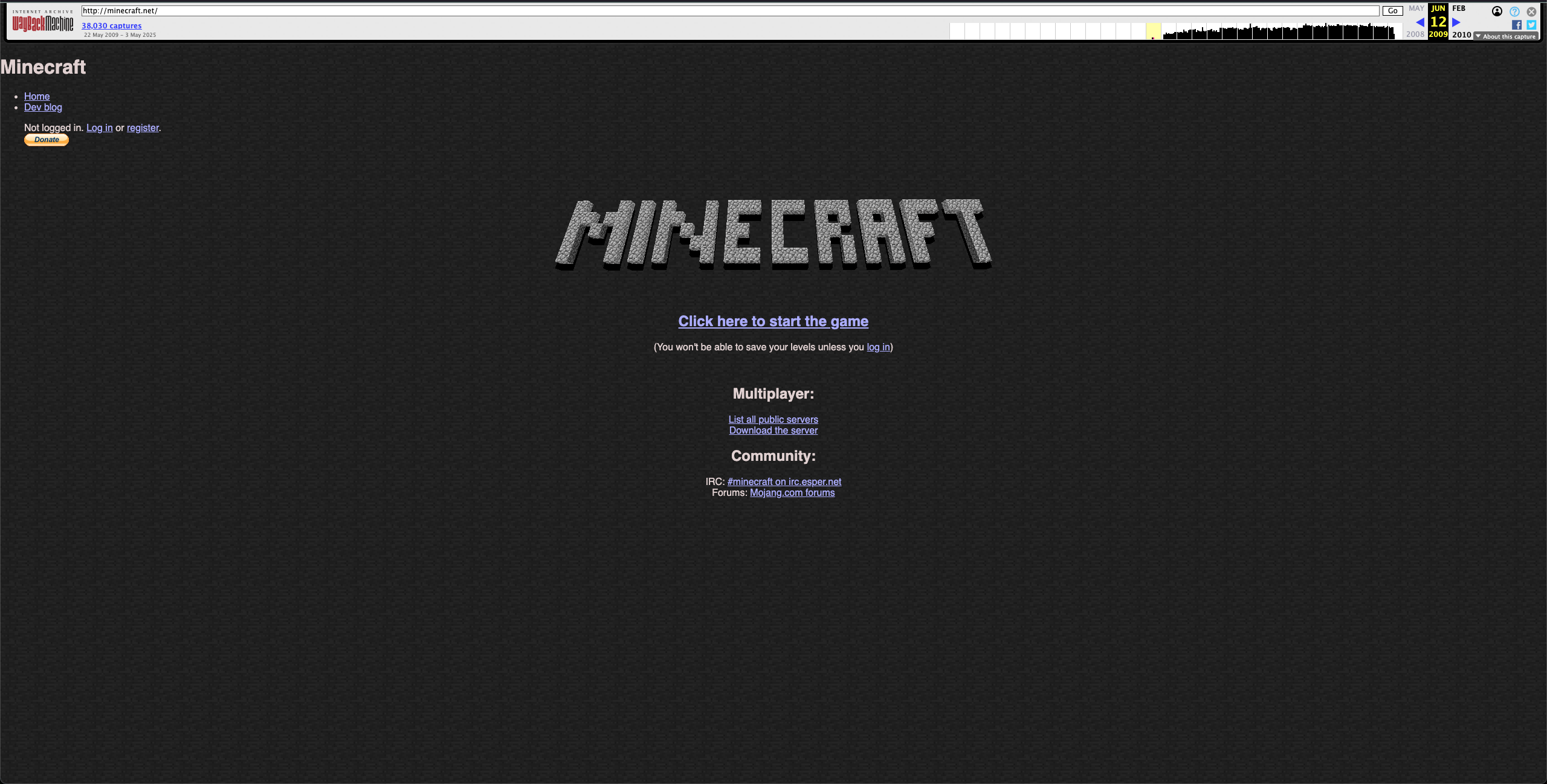

The Internet Archive exemplifies institutional data preservation. It's structured and expansive digital repository encompasses books, multimedia artefacts, software, and even ephemera such as defunct websites. The Wayback Machine, in particular, captures the temporal and ephemeral nature of the internet by maintaining snapshots of webpages, many of which have long since disappeared. A great deal of this media would be entirely lost to time without such efforts.

The Wayback Machine can be used to retrieve old copies of websites otherwise long lost to time. Minecraft's earliest website (minecraft.net) from 12 June, 2009

It is therefore unsurprising that individuals aspire to construct personal archives. Whether through USB drives, external hard disks, or elaborate network-attached storage (NAS) arrays, people increasingly undertake private data preservation. Even absent such hardware, modern productivity ecosystems—from Google Drive to iCloud—automatically synchronise and store significant volumes of both professional and personal data, including images, videos, messages, and notes.

Smartphones, especially within Apple’s tightly integrated ecosystem, serve as near-constant companions, collecting an immense volume of data, often without explicit user intent. Even before factoring in auxiliary data sources like wearables, the capacity of such devices to generate a passive digital record is substantial. While there are legitimate concerns regarding privacy and surveillance, this discussion temporarily suspends such critiques to foreground potential benefits.

Armed with only a smartphone, one can construct a robust chronological account of everyday life. This constitutes a trail of metadata—digital breadcrumbs—that facilitate future reminiscence. These fragments, subtle and often ambient, function as mnemonic scaffolds in moments when one might otherwise have no hope but to say, "I don’t remember". Why might this matter? Perhaps to recount one’s life story with clarity to friends, family, or future generations—free from conjecture. Or perhaps in the face of a diagnosis such as dementia, where the autonomy to remember becomes fragile, and these passive records offer a lifeline to one’s sense of self.

Nonetheless, this practice invites ethical scrutiny. There exists a fine line between supportive cues and surveillance-adjacent intrusiveness. What may feel like an innocuous nudge today may retrospectively appear as overexposure.

I’m always drawn to a good Black Mirror reference, and the episode ‘The Entire History of You’ offers a compelling exploration of how archival can quickly blur into oversurveillance — raising important questions about when preservation becomes intrusive. ScreenRant summary of 'The Entire History of You' (content disclaimer; NSFW & distressing themes)

Analogue media, by contrast, are data-poor: they are largely devoid of metadata. Age, context, and provenance must often be inferred post hoc, from the materials themselves or surrounding evidence. Digital media, enriched with metadata—timestamps, geolocation, and device identifiers—automatically offer contextual anchoring. This additional layer imbues digital accumulation with a form of intrinsic structure and interpretability that distinguishes it from its analogue equivalent.

Consequently, even the most disorderly digital archive—a cluttered desktop, a chaotic folder hierarchy—contains more retrievable meaning than an analogue hoard lacking temporal or contextual cues. Metadata transforms accumulation into something semi-coherent, even when not deliberately organised.

In MyLifeBits [3], a 2001 Microsoft research project, every “life bit” is stored not as a loose file dump but as a richly tagged resource. Each item carries standard properties—type, size, creation date, last-modified date—and a flexible time-interval that anchors the content to the span it actually covers (e.g. the date a photo was taken or the years a document discusses). Yet the project begins from the assumption that users will indeed keep everything—“shoeboxes full of photos, home movies, old bundles of letters…treasured but forgotten”—and that sheer volume alone doesn’t guarantee recall.

To tame this sprawling hoard, MyLifeBits replaces rigid folders with fluid collections (dynamic queries + manual inclusions/exclusions) and lets users filter out unused items or low-rated annotations, so that even a terabyte of “junk” can be sifted down to the handful of cues that spark genuine recollection. In this way, the system occupies exactly that liminal space between indiscriminate hoarding and curated preservation—profligate capture paired with lightweight, metadata-driven scaffolding for reflection.

This brings us back to lifelogging.

Lifelogging operates as an armature: a subtle but pervasive framework underpinning the potential for memory reconstruction. Moments that might otherwise vanish—uncaptured by photos or significant events—are retained ambiently. Periods of illness, social withdrawal, or even simply 'quieter times in one's life' often appear as voids in traditional memory, but may, through passive data collection, reveal patterns of activity or absence that signify their own importance.

BeReal is a prime example of a social media platform which pioneered life-logging–esque sharing, prompting one to take and share a photo at time of the day. When I look back at some of my months on it, I am immediately more drawn to the 'why' for any blanks on the calendar. What was so important, or why was I too lazy to upload then? I wonder what happened on the 19th... BeReal

This latent memory is not narrativised in the conventional sense. It is not authored deliberately but accumulates quietly through metadata: workout logs, mobility patterns, communication histories, and lack thereof. Even an absence of data — the fact I see no BeReal entries for specific days — is indeed in itself a datapoint. It allows me to follow up on aspects such as why these days are indeed empty of entries, permitting further speculation as to what else I may have been doing at that time. Though unstructured and occasionally messy, it has retrospective value.

As with MyLifeBits, I would argue that lifelogging does not neatly fit into the categories of preservation or hoarding—it occupies a liminal space between the two. In many cases, intrinsically, it more closely resembles data hoarding—undifferentiated, sprawling, and potentially somewhat inconsistent. Yet it offers a scaffolding for reflection that traditional hoarding cannot. It enables meaning to emerge from seeming incoherence. Despite the derogatory connotations, it holds the potential to do a world of good.

Should this motivate one to join online data-hoarding communities and construct a personal data centre? Perhaps, perhaps not— but either way, with a measure of discernment. For the technically inclined, this may be rewarding — I speak for myself at least — yet, such measures are not requisite. Simply increasing the retention of latent, ambient data—data which already exists passively—constitutes a significant act. Backing up fitness records, syncing communication logs, or archiving personal documents are all small interventions that cumulatively support future recollection.

The extent and nature of what one chooses to archive can be individualised. There may seem no rationale in preserving data for activities one does not engage in, although it is worth considering the fact that a lack of an activity is inherently a prospective datapoint. A person disinterested in physical activity may disregard workout metrics; a gamer may, instead, retain gameplay statistics, screenshots, or server logs. What matters is aligning data retention with personal relevance.

Music merits a dedicated account in this discussion.

With Spotify now holding a dominant position in the streaming ecosystem, the archival potential of personal music data has become remarkably accessible. Users can retrospectively examine every track they have listened to, along with cumulative insights into their listening habits over time. Given music’s powerful role in triggering autobiographical memory, being able to pinpoint when a particular song featured prominently in one’s life may hold more significance than initially assumed. Crucially, digital metadata allows us to locate these moments with temporal precision—eliminating the guesswork once inherent in recalling when a CD was purchased or an LP was first played. It does in fact already do this, autonomously.

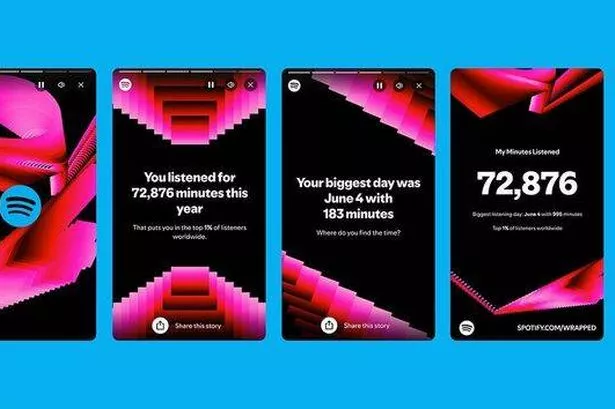

Spotify Wrapped — the end of year musical summary that dominates one's Instagram stories for weeks. Spotify

Spotify Wrapped has become an inescapable cultural event for anyone active on social media. The annual distillation of one’s listening habits into a shareable data narrative offers a compelling, if curated, snapshot of personal engagement with music. It is a moment where a year’s worth of passive interaction is rendered visible—and often, surprisingly meaningful. One cannot help but imagine the potential of such introspection extended across an entire lifetime: a comprehensive auditory archive that not only reflects tastes and trends, but anchors memories to precise temporal coordinates. If you want to do some hoarding of your own listening trends, their publicly accessible API is a fantastic place to start if you are brave, but even if not, many 3rd party tools already offer statistical summaries of your data, saving you getting your hands dirty.

And AI?

I would further argue that artificial intelligence fundamentally transforms data hoarding from a reflexive act of accumulation into a strategically curated process. The perennial uncertainty—of what artefacts will ultimately prove valuable—applies equally to analogue and digital archives. Yet AI’s capacity to ingest, parse, and synthesise vast datasets in real time converts the deferred “I will deal with it later” into a viable computational workflow. Indeed, the data-pipeline architectures under development in my own work demonstrate how intelligent systems can tag, filter, and contextualise raw information streams automatically.

Furthermore, given the rapid and unpredictable advancement of AI—over a five- to ten-year horizon, let alone across decades—it is prudent to adopt a better safe than sorry ethos regarding digital preservation. Retaining rich, even unstructured, datasets today may enable future analytical methods to extract insights that are currently unimaginable. In this light, what might seem like indiscriminate hoarding becomes, instead, a strategic investment in emergent analytical potential.

Do be courteous of GDPR, and don't take this reflection as your directive to save every single file you EVER touch over your entire life span. There are obvious cases of data, i.e. work data, where you should really not be saving it unless permission is expressly given, and even then, you should only be saving and utilising it within the permitted scope of work, on approved storage media.

This reflection is not a justification for violating data protection frameworks, nor does it condone the inappropriate retention of professional data. Such practices are ethically and legally indefensible. I also am not persuading one to begin undertaking unhealthy hoarding of any constitution.

Still, even an unstructured, sprawling repository of passively collected personal data contains the contours of a life. For many, that latent narrative is not only worth preserving—it is deeply human. We have long reconstructed personal histories from fragments: letters, photographs, oral accounts. Yet with the richness of digital metadata, we gain an unprecedented capacity to immortalise the everyday. In such abundance, the digital traces we leave behind could render future ancestry less opaque, transforming mysterious relatives, who may one day be ourselves, into vivid, data-rich presences across time.

Let your digital legacy live on...

References

[1] Gordon Bell. 2010. Your Life, Uploaded: The Digital Way to Better Memory, Health, and Productivity. Penguin Publishing Group, East Rutherford.

[2] r/DataHoarder. Reddit. Retrieved May 5, 2025 from https://www.reddit.com/r/DataHoarder/

[3] Kerry McKellar, Elizabeth Sillence, Nick Neave, and Pam Briggs. 2024. Digital accumulation behaviours and information management in the workplace: exploring the tensions between digital data hoarding, organisational culture and policy. Behaviour & Information Technology 43, 6 (April 2024), 1206–1218. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2023.2205970

[4] Jim Gemmell, Gordon Bell, Roger Lueder, Steven Drucker, and Curtis Wong. MyLifeBits: Fulfilling the Memex Vision.

[5] Vannevar Bush. 1945. As We May Think. The Atlantic Monthly.

[6] Rebecca Stover. 2023. Microfilm Research, Digital Research. Retrieved May 6, 2025 from https://www.library.illinois.edu/hpnl/blog/microfilm-research-digital-research/

[7] Microsoft. 2024. NTFS Overview. Retrieved May 5, 2025 from https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/storage/file-server/ntfs-overview

[8] Filesystems in the Linux Kernel. The Linux Kernel. Retrieved May 6, 2025 from https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v6.1/filesystems/ext4/overview.html#blocks

[9] Jo Ann Oravec. 2018. Digital (or Virtual) Hoarding: Emerging Implications of Digital Hoarding for Computing, Psychology, and Organization Science. International Journal of Computers in Clinical Practice 3, 1 (January 2018), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCCP.2018010103